Several news reports on the current issue (Dias, 2024; Teles, 2024), greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, all based on a report that the European Court of Auditors (ECA) had published on 24 January 2024, came across my radar. All the news stories were similar and concluded the same thing, that the problem lies with combustion vehicles, a conclusion derived from the ECA report. I even came across a news report/interview with Carlos Tavares, CEO of Stellantis, in which he recommended removing the most polluting cars from the car fleet and providing subsidies for people to spend on newer vehicles, thereby reducing emissions from passenger cars.

Regardless of opinions, I was left wanting to expand on the subject, which is the need to reduce GHG emissions from the road transport sector. Furthermore, I had already studied this topic in depth in academic work, specifically on the European Commission’s “Fit for 55” package.

This package in particular is the most pertinent to this issue of emissions in the transport sector, so this article will be based on an overview of this package and I’ll give my opinion at the end.

Firstly, we need to understand how the legislative process, the way laws and regulations are created in the European Union, works and who the players are.

In the European Union (EU), the legislative process is conducted by three important players:

- The European Commission, led by President Ursula von der Leyen, is in charge of proposing new legislation and policies. Made up of a college of commissioners, it plays a key role in formulating EU guidelines.

- The European Council, made up of heads of state or government from each EU member state, defines the bloc’s general political guidelines and priorities. Its deliberations reflect the consensus among national leaders on fundamental issues that shape the direction of the Union.

- The European Parliament, an institution directly elected by the citizens of the EU Member States, plays a crucial role in the legislative process. Responsible for reviewing legislative proposals, this body has the power to impose amendments and vote on them, directly representing the interests and will of Europeans.

This is the EU’s legislative process in a nutshell.

Now, the “Fit for 55” package consists of a set of proposals aimed at revising and updating European legislation and creating initiatives that are in line with the climate objectives agreed by the Council and the European Parliament.

One of the aims of the package is to revise the regulation that sets CO₂ emission performance standards for new passenger cars (PC) and commercial vehicles (CV). With this objective, it aims to reduce the EU’s GHGs by at least 55 per cent by 2030, compared to the 2021 figures. I’ll go into the measures in more detail later.

The package covers several themes:

- Sustainable transport

- Energy sector

- Energy efficiency

- Sustainable industry

- Agriculture and land use

- EU Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS)

- Carbon taxation

- Sustainable finance

- Social protection and climate justice

- Innovation and research

- Air pollution

- Adaptability

- The role of forests

- Maritime and air transport

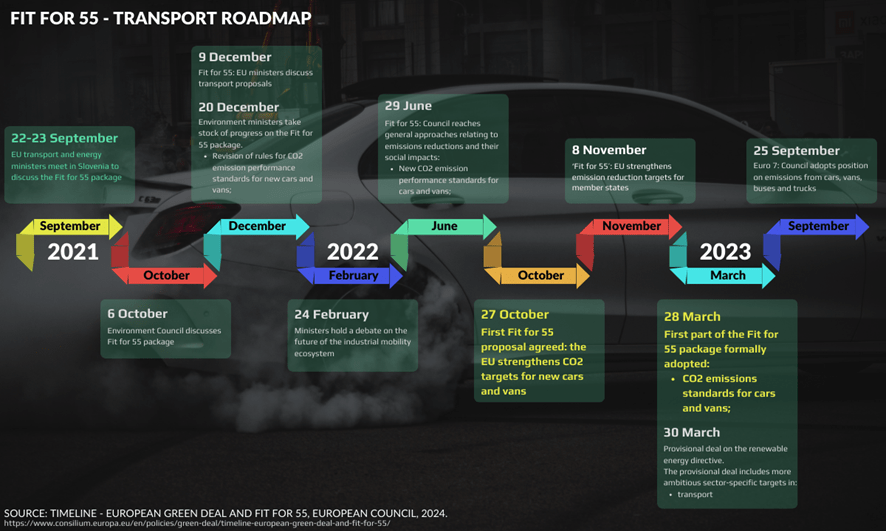

For the subject I’m dealing with here, I’m just going to go into more detail and disseminate information about sustainable transport. Figure 1 shows the stages from the European Commission’s announcement of the package to the most recent one.

I want to emphasise that the timeline shown in the image only refers to the proposals that cover the transport sector, specifically light passenger transport, as there have been many more actions within this timeframe than those shown in the image.

Since its presentation in September 2021, the proposal on CO₂ emissions from new PC and CV within the “Fit for 55” package has taken one year and seven months to be adopted, with amendments.

From the timeline presented, the most important dates are when the package was presented, on 22 and 23 September 2021, and when the proposals were approved, on 27 October 2022 and 28 March 2023.

On October 27ᵗᴴ 2022, the Council and the European Parliament reached a provisional consensus on policies concerning the emissions of new PC and CV. The important word here is “provisional”. On this day, pending formal adoption, the co-legislators agreed on a reduction and the date that should be adopted in the legislation:

- Reduction of CO₂ emissions by 55% for new PC and 50% for new CV by 2030, compared to 2021 levels;

- Aim for a 100% reduction in CO₂ emissions from new PC and CV by 2035.

This proposal outlined in the “Fit for 55” package is highly ambitious, in my opinion, and very unrealistic. I think the Council and the European Parliament should be on the same wavelength as me, given the decision they take at their next meeting.

On March 28ᵗᴴ 2023, the Council adopted 4 of the proposals contained in the Fit for 55 package, the main objective of which is to reduce net GHG emissions in the EU by at least 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. One of the 4 proposals was the regulation on CO₂ emissions from PC and CV:

- A 55% reduction in CO₂ emissions for new PC and a 50% reduction for new CV between 2030 and 2034;

- Finally, a 100% reduction in CO₂ emissions for PC and CV from 2035, compared to 2021 levels;

The GHG reduction figure of 55% compared to 1990 refers to EU emissions. The question here is why did they choose 1990 and not 2021 as the basis for the reduction?

Simple.

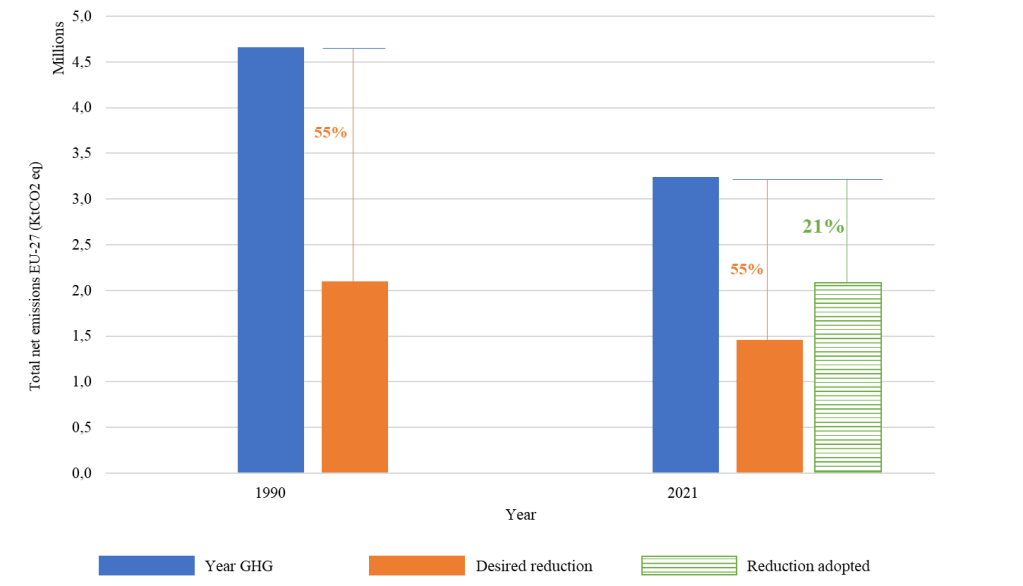

Since the 1990 figure is higher than the 2021 figure, if you apply the same percentage reduction in emissions, you will get a higher target figure than if you had used the 2021 emissions figures as a basis. It’s easier to explain with a graph.

To better demonstrate and explain the scale of the measure, I have created figure 2. Through this, I can better explain the difference between the European Commission’s proposal and what was accepted by the European Council.

In the blue column we can see the value of GHG emissions for 1990 and 2021, the two years used as the basis for the reduction proposals, one by the European Parliament and the other by the European Commission, respectively.

The orange column shows the reduction requested by the European Commission, which is 55 per cent of the GHG emissions for 2021.

The green striped column represents the proposal adopted by the European Parliament, which is still 55% of the emissions figure. The difference lies in the year of the emissions figure adopted, which is 1990. As the 1990 emissions figure is higher than the 2021 figure, the reduction compared to the 2021 figure will not be as drastic. So, compared to 2021, the European Parliament has adopted a 21% reduction.

Now the legislation is on the table. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll use the summary table below to continue.

| Fit for 55 package | PC from 2030 | CV from 2030 | From 2035 |

| 55% below the 2021 limit | 50% below the 2021 limit | 100% reduction |

Who are these regulations aimed at?

These regulations in the “Fit for 55” package are aimed primarily at car manufacturers and the automotive industry as a whole. As you can see, these proposals set strict CO₂ emission standards for new vehicles sold on the European market.

In this way, it is the car manufacturers who are directly subject to the regulations and are responsible for ensuring that vehicles comply with the established standards. This means that automakers must design and manufacture vehicles that meet the CO₂ emissions requirements stipulated in the regulations.

What this package is bringing to the car market is forcing the transition to less polluting means of motorisation in light vehicles, and after 2035, no pollution at all.

What leaves me incredulous is the fact that they are only attacking one part of the manufacturing chain. In environmental terms, during the construction phase, the types of vehicles you want to switch to are drastically more polluting.

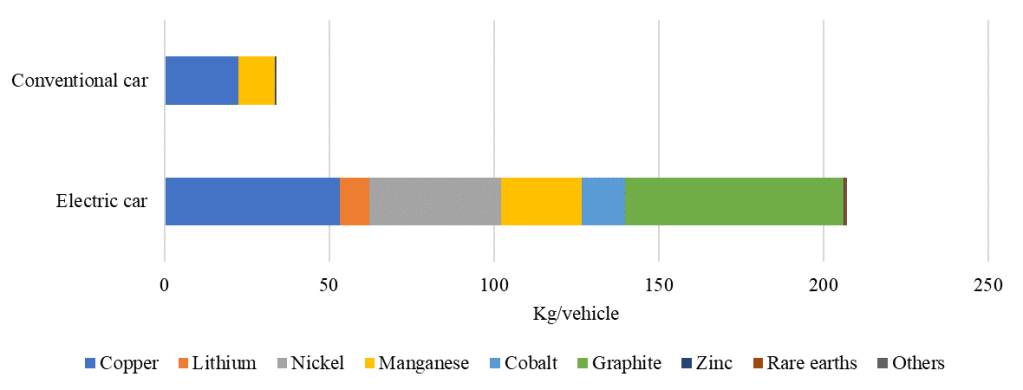

Figure 3 shows the difference in the quantity and diversity of minerals that make up conventional vehicles, internal combustion vehicles (ICVs) and electric vehicles (EVs).

There are two metals that are crucial to both, but they have been left out by the International Energy Agency (IEA): aluminium and steel. However, from other sources, it was possible to estimate part of this gap in figure 3.

With regard to aluminium, according to CRU (2018), each ICV accounts for 160 kg of this metal, while EVs account for between 25% and 27% more aluminium per vehicle than ICVs. As for steel, in general, ICVs are 54% steel (American Iron and Steel Institute, 2018). Given that the average weight of a new ICV in Europe is 1382kg (ICCT, 2020), this results in an amount of steel per vehicle of 746.28kg. On the other hand, EVs have between 40 and 100 kg of non-oriented grain electrical steel (Steiniger, 2019).

Figure 4, which I created, complements the IEA graph with the gaps that were omitted.

Figure 4 shows the differences between the minerals used in the manufacture of each type of vehicle. The difference in the amount of steel between the two types of vehicle is remarkable, with the ICV requiring the greatest amount in its manufacture. However, EVs require a much greater variety of minerals than ICVs, mainly due to the electric battery component. As a result of this need, significantly more CO₂eq is emitted, around 60%, compared to ICVs (Xia and Li, 2022).

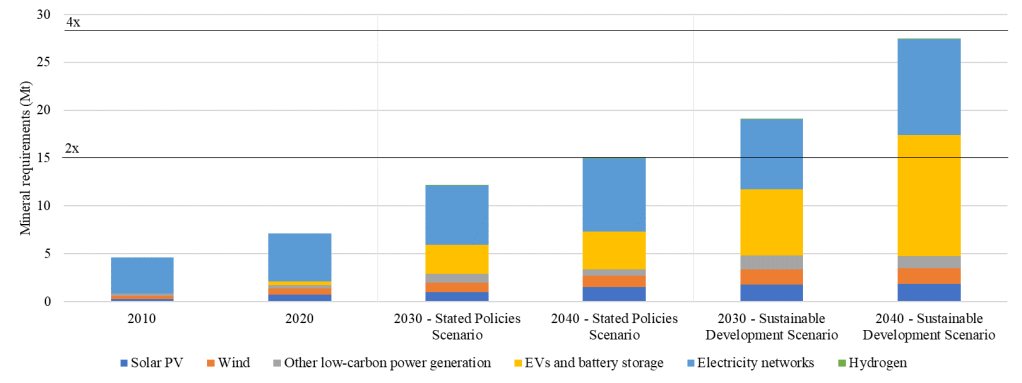

On top of this, with this effort being made to force people to adopt this type of vehicle, there is another fact, expressed in figure 5, which represents the IEA’s projections for the need for minerals over the next 20 years.

I want to emphasise that a projection of mineral demand is highly uncertain, and depends on climate policies and technological development trajectories. However, in addition to the assumptions used as a basis for technological development, the IEA has identified key variables for each technology that can influence mineral demand. They therefore created 11 alternative scenarios to quantify the impact of trends in technological evolution. As well as focussing mineral needs solely on clean energy technologies, they assessed the needs of other sectors to understand the contribution of clean energy technologies. They projected the need for minerals for other sectors based on historical consumption, economic factors and the relevant material intensities, as shown in figure 5.

Thus, it is possible to see the growing pressure that will be imposed on mines that mine the types of minerals previously mentioned in Figures 3 and 4. In both scenarios, EVs and battery storage will account for around half of the growth in demand for minerals from clean energy technologies over the next two decades, driven by increased demand for battery materials.

This impact of mining is included in the construction stage of the EV, making this stage the most polluting in the entire life of an EV.

Obviously, in the next stage of an EV, the use phase, the environmental impacts are almost zero, only the materials such as brakes, tyres, brushes, i.e. components outside the motorisation system. However, due to the high environmental impact in the construction phase, EVs have to cover a certain number of kilometres before they become more “environmentally friendly” than ICVs.

After the use stage, we enter the end of life of the vehicle, specifically the end of life of the vehicle’s batteries, where the greatest environmental impacts come from. Researchers point out that it is this process that claims EVs as the solution for a sustainable transport sector.

From the research I carried out during my master’s degree, I don’t have the same opinion.

The recycling process mentioned by the researchers is related to the idea of mitigating environmental impacts in other areas, such as residential energy storage or public utilities (Xia and Li, 2022). This premise is very fragile, because if there are no applications for the batteries in question, their destination is unknown or facilities capable of carrying out the recycling task are scarce (Yükseltürk et al, 2021).

Added to this, the battery recycling process is currently still very new and full of defects (Yükseltürk et al, 2021), which leads to necessary improvements and further research into more efficient processes with less environmental impact.

Finally, to really achieve a more sustainable road transport sector, we have to reach the entire manufacturing chain, from mining to the end of life of products.

What these measures like “Fit for 55” are really going to achieve is an overstressing of mines and relocating GHG emissions.

The European transport sector is going to reduce its emissions dramatically, while developing countries, where most of the minerals come from, are going to increase their emissions more and more, and many of the mines, since they have no occupational safety supervision, are likely to make people’s working conditions even worse.

I’ll give you the facts, so you can make up your own mind.

Thank you and see you next time.

Leave a comment